Rapid Response Study: Public Health Workforce

Published:

Note: This rapid response study was conducted on behalf of the Center for Health Workforce Studies (CHWS), Albany, as per request from Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) to aid it’s efforts to track the Public Health workforce in the post-pandemic times.

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the urgency for improving our public health infrastructure through investments in expansion of a skilled workforce for future needs. Recently, there has been increased funding into the Public Health and Social Services Emergency Fund and the American Rescue Plan, and these resources are being used towards workforce development activities. For the development of the public health workforce, it is essential to define it, to track it, to know the current efforts to track it and to identify the challenges in doing so. Thus, in this rapid response study on public health workforce, we identify how the “public health workforce” is defined in the current literature, identify the barriers to tracking this workforce, determine what existing data sources exist and note any current efforts to track or quantify it.

Introduction

The public health workforce is indeed essential and the need to recruit, train, and develop a new generation of leaders, who can respond to the nation’s public health needs, is ever present. Specifically, strong public health systems are the first line of defense in a well-functioning health care system. For our nation’s health care system to function in an effective way, we must have skilled and well-supported public health and health education workers (Commission on a Global Health Risk Framework, 2016).

For decades, workforce development has fallen behind due to underinvestment and decreased funding, particularly to our local and state health departments (Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (CDC), 2021). As a result, the nation faced serious consequences during the COVID-19 pandemic; including, insufficient systems for data assessment and monitoring of workforce needs and critical need for more diverse public health and health education workers that can serve our diverse communities. Thus, the public health workforce needs development and support is needed to effectively collect and analyze workforce data on our future needs and to evaluate evidence-based programs for expansion of successful initiatives. Thus, it is imperative to define and track the public health workforce as accurately as possible in order to gauge optimal response during not just pandemic and public health emergencies but at other times too, since public health is an ongoing quest.

Identifying how public health workforce is defined in the current literature

Public health workforce is a broad term and encompasses a diverse range of professions, settings, and focuses. In order to define and track the public health workforce, is it essential to know what constitutes public health.

In 1920, Charles-Edward A. Winslow defined public health as “the science and art of preventing disease, prolonging life, and promoting physical health and efficiency through organized community efforts for the sanitation of the environment, the control of community infections, the education of the individual in principles of personal hygiene, the organization of medical and nursing service for the early diagnosis and preventive treatment of disease, and the development of the social machinery which will ensure to every individual in the community a standard of living adequate for the maintenance of health.”

As opposed to medical care which focuses on an individual, the focus of public health is “population” (Gebbie et al 2002). CDC foundation defines public health as “the science” of protecting and improving the health of people and their communities. This work is achieved by promoting healthy lifestyles, researching disease and injury prevention, and detecting, preventing and responding to infectious diseases.

CDC foundation further elaborates on what public health professionals do. Public health professionals try to prevent problems from happening or recurring through implementing educational programs, recommending policies, administering services and conducting research—in contrast to clinical professionals like doctors and nurses, who focus primarily on treating individuals after they become sick or injured. This definition contrasts public health professionals with clinical professionals. The wider circle of professionals associated with public health includes almost all physicians, dentists, and nurses, plus many other health, environmental, and public safety professionals (Gebbie et al 2002). Public health also works to limit health disparities. A large part of public health is promoting health care equity, quality and accessibility.

Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) definition

The Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) defines public health workers as all those responsible for providing the essential services of public health regardless of the organization in which they work. The 10 Essential Public Health Services (EPHS) describe the public health activities that all communities should undertake. For the past 25 years, the EPHS have served as a well-recognized framework for carrying out the mission of public health. The EPHS framework was originally released in 1994 and more recently updated in 2020.

Shortcomings of the DHHS definition

This definition is very broad in scope, and we lack sufficient data sources to allow for inclusion of the entire public health workforce as defined by DHHS (Strategies for Enumerating the U.S Governmental Public Health Workforce, 2012, pg. 11, para 1). At the same time, this definition doesn’t specify the precise requirements pertaining to the profession, setting, or focus of concern, which makes it hard to track or enumerate public health workforce and is thus prone to inclusion and exclusion errors.

Three dimensions to define Public Health workforce

Gebbie et al (2002) in “The Public Health Workforce” don’t really attempt to redefine public health workforce but give the three dimensions based on which public health workers may be defined. Those dimensions are - specific profession (the worker), place of employment (the work setting), or focus of concern (the work).

Shortcomings of the approach mentioned in Gebbie et al (2002)

A choice of any one of the dimensions given in Gebbie et al (2002) to classify or define public health workforce is problematic because these essentially share complex interdependence between each other. For instance, people belonging to different professions could work in the same setting while healthcare workers belonging to the same professions could work in totally different settings. Similarly, healthcare workers belonging to a specific profession might have a certain focus in a particular setting while other healthcare workers belonging to the same profession might have a completely different focus in the same or different setting.

A healthcare worker involved in a specific profession could be a public health worker by specialty (focus), while another healthcare worker involved in the same profession might not be a public health worker by specialty. For instance, a Registered Nurse (RN) could have acute/critical care, medical surgical care, public health or any other specialty as their “primary nursing position specialty”. Thus, a RN may or may not have “public health” as a primary nursing position specialty. As the table here from the 2020 National Nursing Workforce Survey, Journal of Nursing shows, even though public health specialty constitutes less than 2% of all specialties, the estimated population proportion is more than 40,000. Thus, blanket inclusion or exclusion of a profession could lead to significant inclusion and exclusion errors respectively, in enumerating public health workforce.

Similarly, if we are considering public health setting rather than a specialty, a RN may have “public health” as their “primary nursing practice position setting” while another RN might have a different primary nursing practice position setting such as hospital, community health, nursing home/extended care and so on. This is further complicated by the fact that a RN may have public health as their “secondary nursing practice position setting” while another RN may have a different secondary nursing practice position setting. Thus, as pointed out before, blanket inclusion or exclusion of a setting could lead to significant inclusion and exclusion errors respectively, in enumerating public health workforce.

At the same time, it is important to look at jurisdiction. Even while looking at jurisdiction, we still need to look at the focus. As pointed out before, community health professionals also work at CDC (federal jurisdiction), but their focus isn’t the same as public health professionals. In conclusion, while enumerating the public health workforce, it is important to take into consideration all the following - profession, setting or jurisdiction and focus of concern or specialty.

NY State Department of Health occupational categories and focus

There have many attempts internationally as well as at state level in the U.S. to define, enumerate or classify public health workforce. One of the useful ones is by the NY State Department of Health, which is more specific as regards to the focus or activity of each of the public health employee. NYSDOH doesn’t really define public health but lists the professions with certain professions who need to have a specific focus to be classified as “public health employees”.

According to NYSDOH, the public health employees include:

- Scientists who go out and track the source of diseases.

- Nurses who administer vaccinations in clinics and conduct home visits to assist new babies.

- Sanitarians, technicians and engineers who make sure certain restaurants are clean and drinking water is safe.

- Nutritionists who develop recommendations for healthy eating.

- Laboratory scientists who test water, foods and specimens for contamination.

- Health educators who promote and improve health by teaching individuals, families, groups and communities how to assume responsibility for addressing health and healthcare issues.

NY state department of health mentions public health professionals separately and they include-health commissioners/directors, public health sanitarians, public health technicians or engineers, public health nurses, epidemiologists, public health educators, doctors, nutritionists, scientists and dentists.

Shortcomings of the NYSDOH list

The NYSDOH list of public health employees and the tasks they should be doing and that of the professionals is specific. However, it doesn’t specify the settings or jurisdiction for these public health employees or professionals, which could make the task of tracking the public health workforce difficult. Moreover, the current data sources are limited to not allow us to track the public health workforce based on job focus.

Public health workforce taxonomy

Public health workforce taxonomy is a standardized multi-axial taxonomy to facilitate the systematic characterization of every public health worker, and a set of minimum data elements to be incorporated into future public health workforce surveys by the University of Michigan Center of Excellence in Public Health Workforce Studies (UM CEPHS), supported by CDC and HRSA funding. The taxonomy is designed to improve the comparability among public health surveys collecting workforce data and assist with difficult enumeration problems, although identity resolution is not a specific feature of this taxonomy. The public health workforce taxonomy is not an attempt to develop a new set of standard occupational classifications for public health; rather, it serves as a tool for post-coordination of public health worker characteristics regardless of the differences in the occupational classifications applied (Boulton et al 2014). The 12 axes of the workforce taxonomy are occupation, workplace setting, employer, education, licensure, certification, job tasks, program area, public health specialization, funding source, condition of employment, and demographics.

Case Definition Used by the 2010–2011 COE Project

The case definition tackles some shortcomings described above as well as some other challenges. It was drafted by the core teams from University of Michigan, University of Kentucky, CDC, and HRSA based on available data sources; NACCHO and ASTHO provided feedback on the draft. It is important to specify that the case definition focuses only on the governmental public health agencies - both public health as well as nonpublic health - at all levels viz. Federal, state, local. It excludes non-governmental agencies or public health professionals employed in private settings. This would make the task of enumerating or tracking the public health workforce much easier if properly coordinated with the survey organizations.

The case definition for a public health worker includes all persons responsible for providing any of the 10 Essential Public Health Services (defined earlier) who are employed in the following venues:

- Traditional nontribal state, territorial, and local governmental public health agencies/departments

- Federal agencies with a clear mandate to provide public health services

- Non–public health state, territorial, local, or federal governmental agencies providing environmental health services

- Non–public health state, territorial, local, or federal governmental agencies providing public health laboratory services

15 occupational classifications have been identified as part of the project case definition, to match the occupational classifications developed for ASTHO and NACCHO’s profile surveys. These are as follows:

- Administrative or Clerical Personnel

- Behavioral Health Professional

- Emergency Preparedness Staff

- Environmental Health Worker

- Epidemiologist

- Health Educator

- Laboratory Worker

- Nutritionist

- Public Health Dentist

- Public Health Manager

- Public Health Nurse

- Public Health Physician

- Public Health Informatics Specialist

- Public Information Specialist

- Other Public Health Professional/Uncategorized Workers

The definitions of each of these classifications could be found in Appendix in Strategies for Enumerating the U.S. Governmental Public Health Workforce, 2012. This project used the occupational titles used in the Enumeration 2000 study, which used 55 occupational titles adapted by the Center for Health Policy (CHP) at Columbia University from a taxonomy of titles developed by HRSA’s Bureau of Health Professions. Selected categories were modified because of changes in the SOCs during the past decade, and categories were condensed or eliminated to 20 occupational categories. The occupational categories were grouped into 15 occupations because they were determined by consensus to be the prime data sources for this project and were developed through a structured data harmonization process.

Shortcomings of case definition approach

The final classification in the case definition excludes important categories from the original 55 categories from 2000 Enumeration Study which are directly involved in delivering public health related care such as infection control/disease investigator and health planner/researcher/analyst and includes nearly all of the peripheral public health workforce or workers which are directly not involved in public health activities but rather in general activities meant to support the public health professionals such as all the clerical staff or administrators.

Although these classifications work well for state and local health department personnel, they are more difficult to apply to the OPM (Office of Personnel Management) Occupational Series, which provides more specificity than the broad OPM categories used in Enumeration 2000.

Several of the public health workers are not included in the case definition approach. They are as follows:

- Community Health Workers

- Faculty and Students in Schools and Programs of Public Health

- Public Health Workers in Private Settings

- Medicaid Workers

- School Health Workers

- Public Health Workers Providing Clinical and Population Health Services

- Tribal Public Health Workers

- Volunteer Public Health Workers.

Several of the public health workers are uncounted or undercounted due to gaps in data collection. Gaps in data collection include the limited information about the tribal public health workforce (additional data sources should be identified) and the lack of data on multiple occupations in all industries. Overall, the biggest challenge with enumerating the public health workforce by using existing data sources is filtering out those who are not public health workers in the BLS data and reconciling discrepancies in counts from different sources to determine where workers are undercounted, overcounted, and double-counted (Strategies for Enumerating the U.S. Governmental Public Health Workforce, 2012, pg. 17, last para).

For physicians, the NACCHO and ASTHO surveys do provide a count of the FTE public health physicians, public health nurses, public information specialists and so on. But there is little clarity about categorizing other professions such as physician assistants, behavioral health staff, quality improvement specialist and so on. The 15th category among the categories of occupations in the case definition i.e. “Other Public Health Professional” or “Uncategorized Workers” is very open-ended and provides no clarity on who should and should not be included in this group. Thus, another challenge is to decide whether everyone in the public health setting be classified as a public health worker or not.

Public health workers uncounted or undercounted in case definition approach

Public health workers uncounted or undercounted in the case definition approach are as follows:

- Federal Non- civilian Employees

- Contract Employees

- State and Local Governmental Public Health Workers

- Environmental Health Workers and Sanitarians

- Laboratory Workers.

Public health workers who are double counted in case definition approach are:

Public health workers who are double counted in the case definition approach are:

- District of Columbia Health Department Workers

- Federal Civilian Employees

The case definition mentioned above only marks the first phase of the public health workforce enumeration strategy which is slated to expand as data sources become refined and readily available. The first phase only identifies the “core” of the public health workforce for whom data is readily available. In phase II, the case definition would expand to focus on governmental workers for whom no workforce data source exists, CHWs employed in nongovernmental organizations, and public health faculty and students. The third phase of the case definition might include tribal public health workers and public health workers in private agencies and the health care system. Finally, the broadest phase of the case definition might capture the remaining sectors of the public health workforce that are more difficult to identify such as volunteer workers or CHWs not employed by an agency or organization, local boards of health members, and public health workers in schools).

Barriers to tracking the public health workforce

The efforts to track the public health workforce have been hampered by a considerable lack of data about the public health workforce. Knowledge is limited regarding the workers the workforce comprises — how many workers populate it, what disciplines are represented, where workers deliver essential services, or how effective they are at doing so and the demographics of the workers (Strategies for Enumerating the U.S. Governmental Public Health Workforce, 2012, pg. 6, para 2).

Governance structures in public health systems are complex – some are centralized, and some are decentralized, with different jurisdictions. State workers have different functions than local and federal. So, defining, tracking or enumerating based on focus or function creates confusion.

The breadth of the field, its multidisciplinary nature, diverse settings for employment, and lack of applied standards for case definitions, worker classifications, or data collection methods are factors that make quantifying and characterizing this workforce difficult. Further, lack of a standardized national public health workforce monitoring system for collecting data in a systematic, consistent way has hampered researchers’ ability to develop reliable estimates. The lack of enumeration estimates jeopardizes the ability of public health leaders to understand workforce capacity, project trends, and develop policies regarding the future workforce. (Enumeration of the Governmental Public Health Workforce, 2014).

A further challenge involves clear demarcation between specialties and settings such community health and public health. In the United States, most public health initiatives fall under the jurisdiction of federal departments of public health, such as the CDC or the Food and Drug Administration. Many public health professionals work in offices and laboratories with local or state health departments, hospitals, and colleges and universities. By contrast, community health professionals often work on a more localized scale, from state and county jobs to local hospitals (though some community health professionals also work at the CDC). (Understanding the Difference Between Public Health and Community Health, Advent Health University, 2020). The community health comprises of preventive, promotive, curative and rehabilitative health services. Thus, only first two overlap with public health. Inclusion of entire community health workforce in public health workforce would cause inclusion of curative and rehabilitative components of community health, which should not be part of public health workforce.

Further, the education and training background of the worker might not coincide with his or her profession or job function. For example, a nurse might function as an epidemiologist in a local health department but have no formal training in epidemiology. These varying definitions should all be considered simultaneously, and piecing together an accurate enumeration from existing data sources, which primarily focus on job title, is difficult (Strategies for Enumerating the U.S. Governmental Public Health Workforce, 2012, pg. 8, para 2).

As has been witnessed during the pandemic, the private or non-governmental organizations involved in public health played a pivotal role. For instance, the activity of administering vaccines is essentially a public health activity. At the same time, the laboratory activity of creating vaccines or finding a cure for infectious diseases is also a public health activity. By this rationale, the workforce in pharmaceutical companies and private labs doing research on infectious or non-infectious diseases becomes a public health workforce.

The role of the private sector in public health is more significant than many people realize. When public health care facilities can’t meet the needs of patients, the private sector will develop a plan to work alongside publicly funded organizations. The private sector is often included as part of the public health’s supply chain. Government funded medical organizations can face more red tape than private health care groups. Due to this, many gaps left by public health organizations can be filled by private health care groups. However, there is a lack of significant efforts aimed at enumerating the public health workforce in non-governmental settings. None of the above-mentioned definitions make attempt at including this workforce.

Virginia C Kennedy, in Public Health Workforce Employment in US Public and Private Sectors, highlights the need for a better understanding of the work performed by public health occupations in nongovernmental work

settings. However, there are other concerns that prevent the inclusion of private organizations as part of official public health delivery systems. According to Business and Human Rights Resource Center, over the last two decades, the private sector has emerged as the world’s top source of financing and leadership in the fight against deadly disease. However, the companies most active in global health projects today hail from a narrow range of industries, many of which are under fire for their negative impact on public health and that their core financial interests are directly at odds with the business of improving the health of the poor. Thus, there is lack of certainty whether the private sector could really be relied upon and could be considered part of public health system.

Since the Public Health Workforce: Enumeration 2000 and Strategies for Enumerating the U.S. Governmental Public Health Workforce, 2012 have been published, research has been modest, underfunded, and mostly sporadic, and it has lacked any type of coordinated approach.

Conclusion

In conclusion, it can be said that apart from inadequate data and uncoordinated surveys, the main challenge still lies in defining the public health workforce. Once it is defined with specificity, that will give clarity on which settings and professions to include or exclude. To sort out public health workers (those with public health as focus) from the collected data, we could use the public health workforce taxonomy to exclude those who don’t fit our definition of public health workforce. Now some questions as far as defining the public health workforce or public health remain. Does public health deal only with prevention or does it deal with cure too? Does public health deal only with infectious diseases or non-infectious diseases too?

According to a recent McKinsey report, governmental public health is charged with a broad mandate: health promotion, health protection, and disease prevention. However, these are again very broad terms. Which activities exactly constitutes health promotion, health protection or disease prevention? Which professions are supposed to carry out these activities and which professions to include or exclude? Should all the peripheral positions or professions (which donor need any medical or public health training) such as clerks, receptionists, administrators, finance professionals etc. be included? Again, community health and public health are two different specialties and settings, and both have different focuses. Should community health workers be really included in the public health workforce as the case definition is slated to do in near future? These and other questions need to be decisively answered before attempting to coordinate and harmonize with the survey organizations.

A more helpful approach would be to separate out the promotive and preventive parts of public health care, while focusing only on the infectious diseases and enumerating only those. It would be helpful to do the same with the community heath too, so that only the preventive and promotive components of both public health and community health can be clubbed together. The public workforce with the sole focus of prevention of infectious diseases and involved in scientific efforts in doing so, could be considered as the “core” or “tier 1” component of the public health workforce. Part of the public health workforce involved in scientific efforts at preventing non-infectious diseases could be classified as “semi-peripheral” or “tier 2” component. Part of the public force directly involved in non-scientific prevention efforts at prevention as well as promotion efforts could be classified as “peripheral” or “tier 3” components. Any such effort at classification or categorization should be done in coordination with the survey organizations.

Existing Data Sources

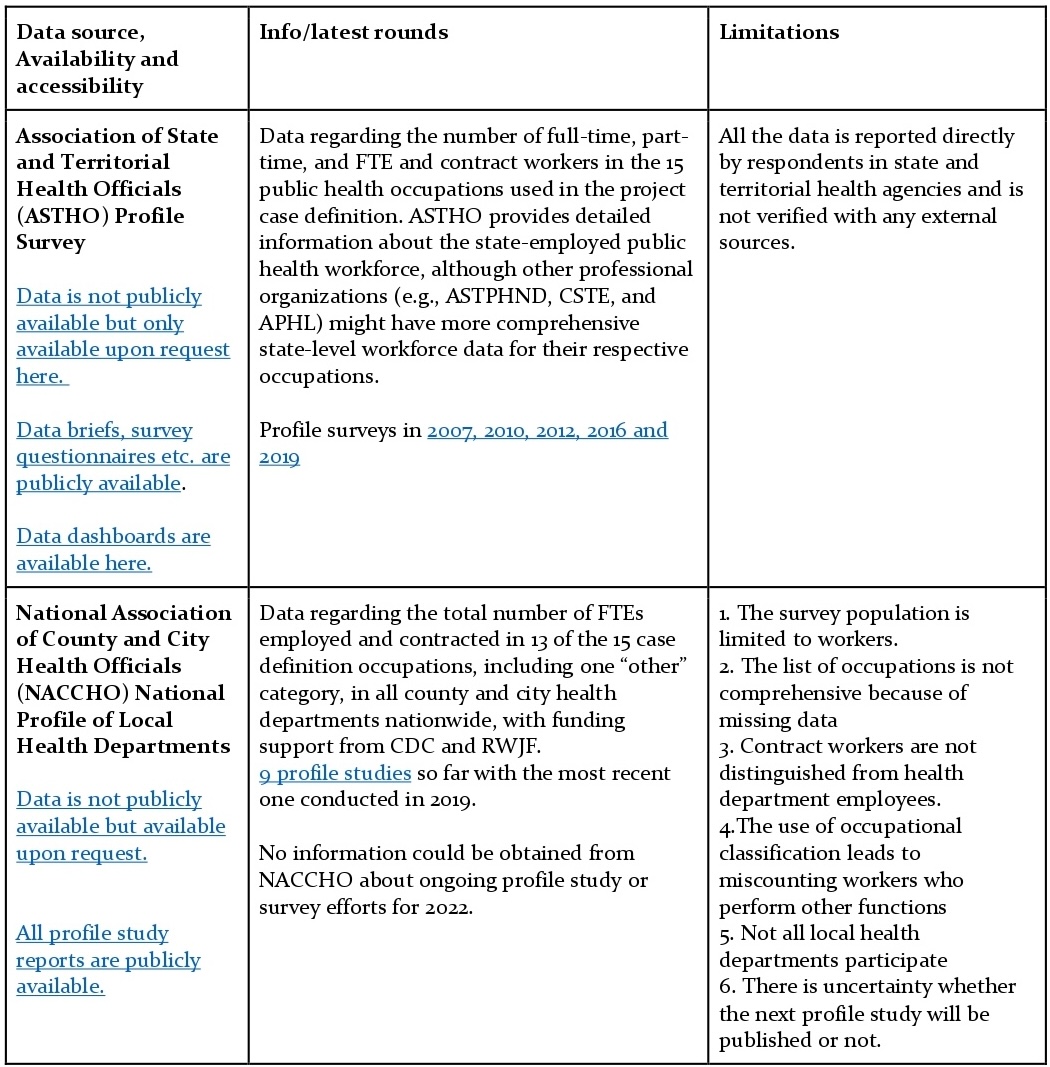

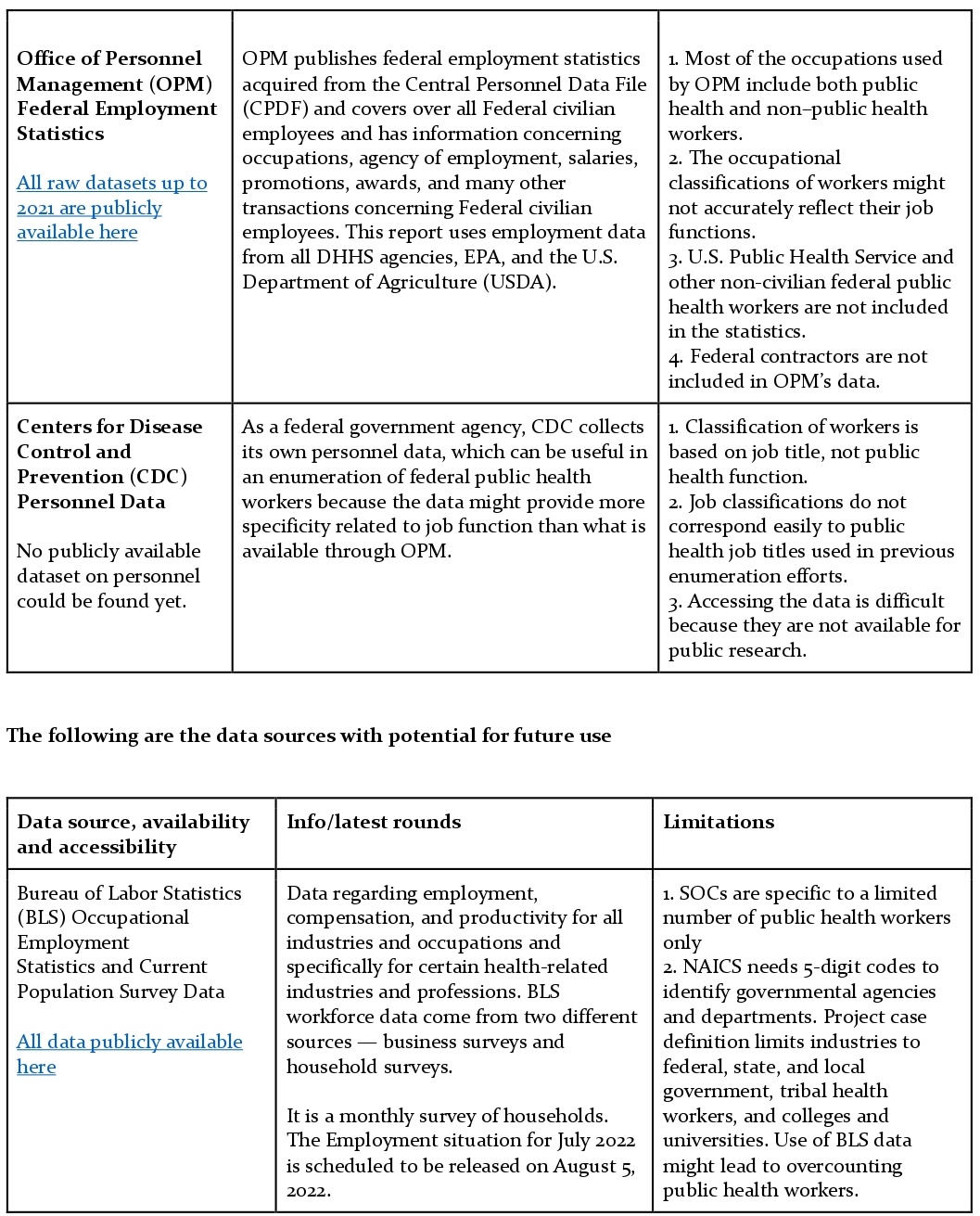

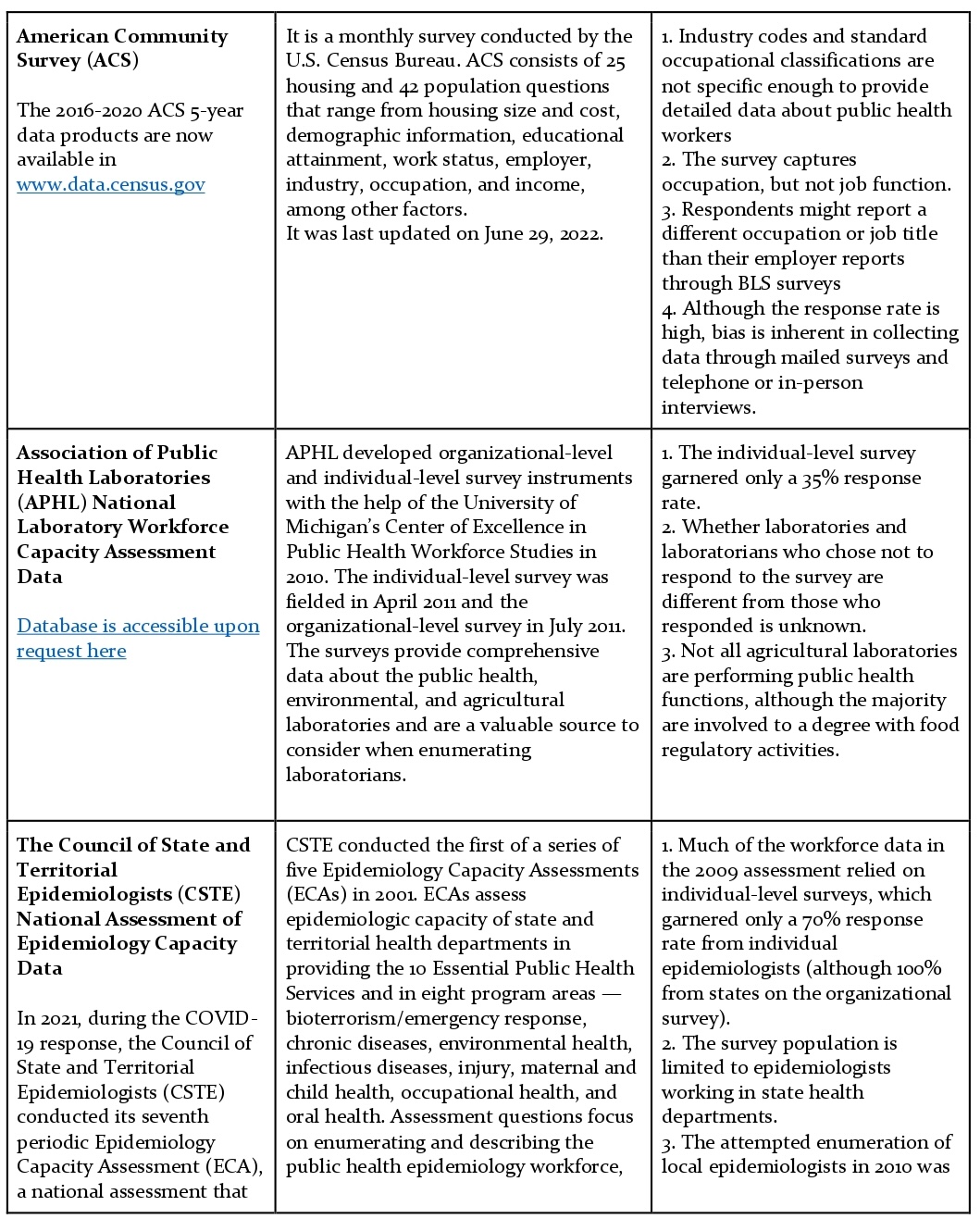

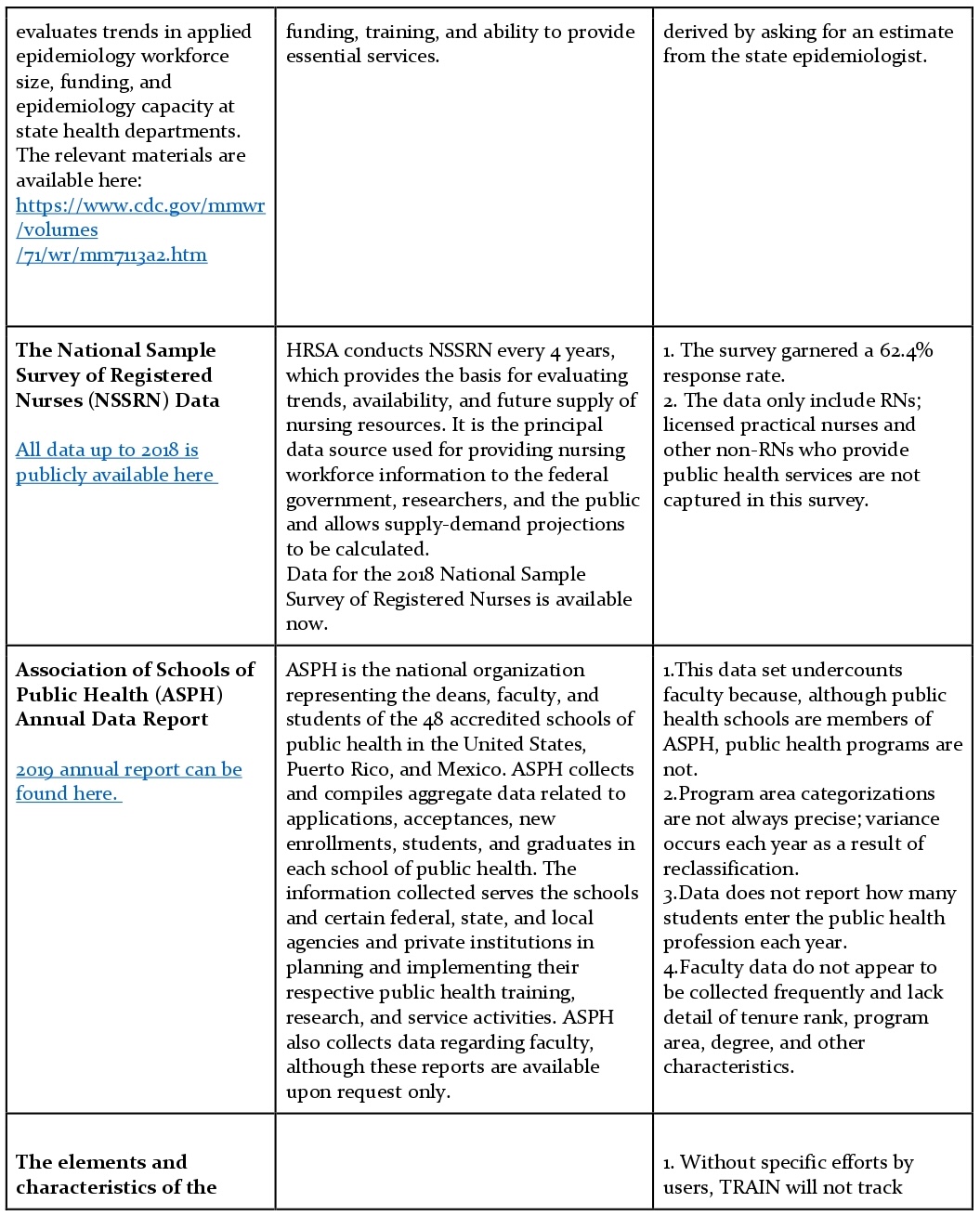

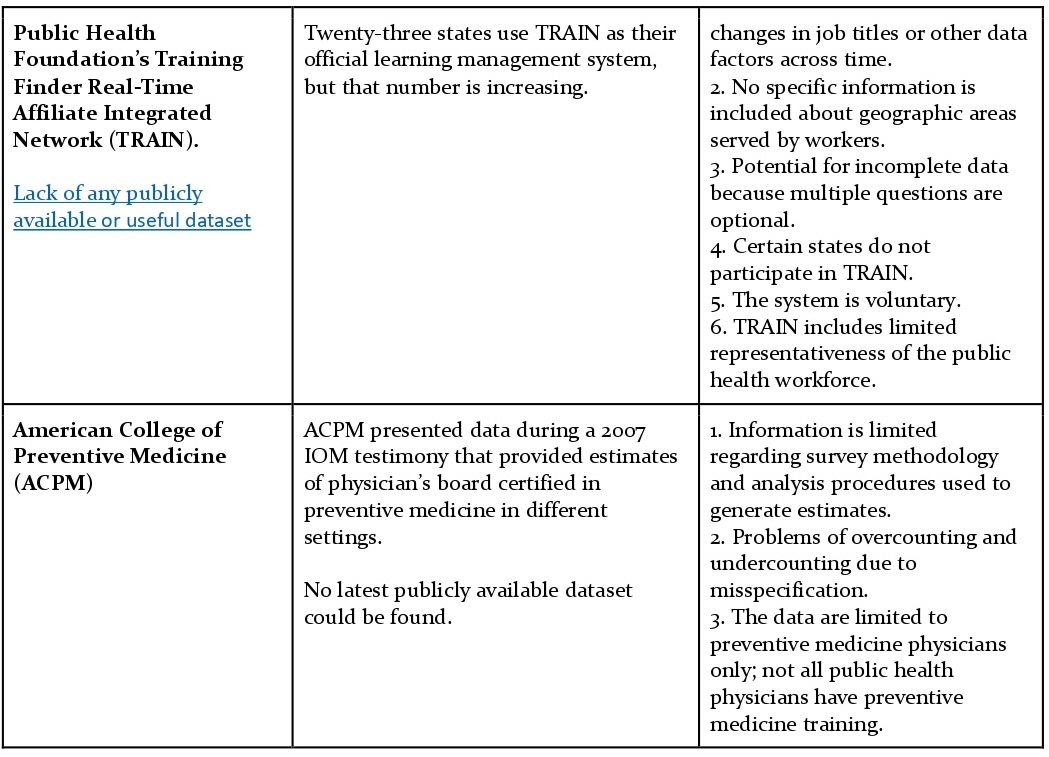

Strategies for Enumerating the U.S. Governmental Public Health Workforce, 2012 categorizes and reflects on the usability of those datasets. Some of these data sources have been classified as available for immediate use, while others need additional research to be available for immediate use.

Data sources available for immediate use are as follows:

Data Sources Not Recommended for Enumeration (Workforce Surveillance as per Strategies for Enumerating the U.S. Governmental Public Health Workforce, 2012)

Association of State and Territorial Dental Directors Data Association of State and Territorial Dental Directors data include state dental directors who hold a public health degree. This information is of limited use because the sample is narrow and based only on educational credentials. Possibly, other dental directors function as public health dentists, despite having no formal public health degree. However, these data might be used as a starting point because BLS does not collect data specifically on public health dentists. ASTHO likely provides more accurate data.

Additionally, there are other available data sources/reports as part of ongoing efforts which potentially might be helpful in public health workforce enumeration or tracking. They are as follows:

The Public Health Workforce Interests and Needs Survey (PH WINS)

PH WINS is the first and only nationally representative source of data about the governmental public health workforce. It captures individual governmental public health workers’ perspectives on key issues such as workforce engagement and morale, training needs, emerging concepts in public health, and collects data on the demographics of the workforce. PH WINS, a partnership with the Association of State and Territorial

Health Officials (ASTHO), was fielded in 2014, 2017, and 2021. Preliminary findings on stress, burnout, and intent to leave were released in March 2022. Detailed national, state, and local findings will be released in summer 2022 (The State of the US Governmental Public Health Workforce, 2014-2017).

The survey is the field’s first large-scale effort to create a nationally representative sample of governmental public health staff at the state and local levels; it is designed around 4 primary domains: training needs, workplace environment, emerging concepts in public health, and demographics. The instrument incorporated several previously used items, including the Federal Employee Viewpoint Survey, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC’s) Technical Assistance and Service Improvement Initiative: Project Officer Survey; the 2009 Epidemiology Capacity Assessment; the Public Health Foundation Worker Survey; and the CDC and University of Michigan Public Health Workforce Taxonomy. However, the survey isn’t useful for tracking or enumeration of public health workforce.

Directors Assessment of Workforce Needs Survey (DAWNS)

In 2017, the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials (ASTHO) fielded the Directors Assessment of Workforce Needs Survey (DAWNS) pilot study to understand state public health leadership perspectives such as barriers to staff recruitment, drivers of turnover, and workforce training needs. ASTHO invited member organizations of its Affiliate Council to participate in the Directors Assessment of Workforce Needs Survey (DAWNS). The goal of DAWNS was to contribute to a comprehensive analysis of public health workforce training needs, gaps, and priorities by incorporating perspectives from public health managers and leaders. Some ASPHN members completed the DAWNS survey. DAWNS builds on the results of the 2016 Workforce Gaps study and complements ongoing workforce development research, including the Public Health Workforce Interests and Needs Survey (PH WINS), which focuses on individual practitioner perspectives. DAWNS was designed to address three primary questions: 1) Leadership perception of training needs 2) Barriers to recruitment and retention 3) The value of formal public health education. DAWNS Summary report is publicly available here

Current efforts to track/quantify public health workforce

As pointed out before, the case definition developed for the 2010–2011 COE project represented the first phase of a public health workforce enumeration strategy that will be enhanced and expanded as data sources become more refined and readily available. By starting the project with a focus on a core public health workforce for whom data can be identified, we can better hone a methodology for ongoing workforce enumeration and surveillance (Strategies for Enumerating the U.S. Governmental Public Health Workforce, 2012, pg. 20, last para).

Apart from the case study definition, all the ongoing survey efforts mentioned above count among the current efforts to track and quantify public health workforce. Additionally, the U.S Department of Health and Human Services’ (DHHS) Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (ODPHP) has “monitoring and understanding of the public health workforce” as one of its Healthy People 2030 objectives. This objective has a research status which implies that it is a “high-priority public health issue” that doesn’t yet have evidence- based interventions developed to address it. Depending on whether baseline data and evidence-based interventions become available, this objective may become a core “Healthy People 2030 objective.”

References

A Brief History of Public Health, MPH modules

A Brief History of Public HealthGebbie, Kristine, et al. “The Public Health Workforce in the Year 2000.”

Journal of Public Health Management and Practice, vol. 9, no. 1, 2003, pp. 79–86.

JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/44968225. Accessed 26 Jul. 2022.Gebbie, K., Merrill, J., & Tilson, H.H. (2002).

The public health workforce. Health Affairs, 21(6), 57-67.Strategies for Enumerating the U.S. Governmental Public Health Workforce, 2012

Strategies for Enumerating the U.S. Governmental Public Health WorkforceCenters for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 10 Essential Public Health Services.

National Public Health Performance Standards Program. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2020.

Available at: CDC WebsiteBuilding an Effective Workforce: A Systematic Review of Public Health Workforce Literature 2012.

American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 42(5 Suppl 1):S6-16.Beck, A.J., Boulton, M.L., Coronado, F. (2014).

Enumeration of the governmental public health workforce, 2014. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 47(5 Suppl 3):S306-13.

PMID: 25439250; PMCID: PMC6944190.

NCBI ArticlePublic Health Workforce Taxonomy - Beck, A.J., Boulton, M.L., Coronado, F. (2014).

Enumeration of the governmental public health workforce, 2014. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 47(5 Suppl 3):S306-13.

PMID: 25439250; PMCID: PMC6944190.

PMC ArticleStakeholders and Core Sciences.

CDC DocumentASTHO Profile of State and Territorial Public Health (ASTHO Profile).

Health PeopleSellers, K., Leider, J.P., Gould, E., Castrucci, B.C., Beck, A., Bogaert, K., Coronado, F., Shah, G., Yeager, V., Beitsch, L.M., Erwin, P.C. (2019).

The State of the US Governmental Public Health Workforce, 2014-2017. American Journal of Public Health, 109(5):674-680.

PMID: 30896986; PMCID: PMC6459653.

NCBI ArticleKennedy, V.C. (2009).

Public health workforce employment in US public and private sectors. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice, 15(3):E1-8.

doi: 10.1097/01.PHH.0000349744.11738.25. PMID: 19363392.How Private Companies are Transforming the Global Public Health Agenda - A New Era For the World Health Organization - Sonia Shah, November 9, 2011.

Foreign AffairsUnderstanding the Difference Between Public Health and Community Health, Advent Health University, 2020.

Advent Health University BlogAll Nursing Stats.

USA BlogCare for the caretakers: Building the global public health workforce - July 26, 2022.

McKinsey ArticleMonitor and Understand the Public Health Workforce — PHI R04.

Health People ObjectiveKey Definitions.

Law InsiderData Source - Public Health Physician Demographics.

ZippiaASPPH - Annual Report 2019.

ASPPH Annual ReportOffice of Personnel Management (OPM) Federal Employment Statistics.

OPM DataNACCHO Profile Data.

NACCHO Data RequestsHRSA Public Health Training Program.

HRSA ReportRegional Public Health Training Centers Program.

HRSA ReportPrimary Care and Public Health Integration.

Google DrivePublic Health Workforce Future McKinsey Report.

McKinsey ReportAchieving Health Equity through Public Health Workforce Diversity (2016).

CDC Report